The pickup truck trailering the last load of eggs plied through rain, framed by a gray dawn on its run from Missouri’s farmland toward Kansas City.

The man at the wheel — farmer Tim Aulgur of Marshall, Mo., — could think about it two different ways, and he chose to feel grateful.

It was a choice, he said, to think warmly about what local farms like his had been able to do with the help of the U.S. Local Food Purchase Assistance program. The federal funding, coordinated statewide by the Missouri Department of Social Services through the state’s Community Partnership Network, had bolstered Aulgur’s young farm with the opportunity to deliver healthy food into low-income communities through schools, churches and food pantries.

But this good fortune for farmers and hungry families was fleeting. The funding is gone now, ended after three years. And as he watched the wet highway roll under his headlights, Aulgur also felt sadness.

The farmers get only a glimpse of the thousands of Missourians who receive the LFPA program meals, but they know they are out there. Before this last rainy day was done, eggs from Aulgur Livestock, along with beef from Hertzog Meat Co. in Butler and Paradise Locker Meats in Trimble, Mo., would be gathered by LINC, the area Community Partnership, and then sacked and taken home by people like Anna Owens and Maxine Mims.

The two women picked up their food at King Elementary in the Kansas City Public Schools where they earn a small stipend amounting to $4 an hour for part-time work in the Foster Grandparents tutoring program.

They love helping the kids. It’s good work, they say. But the truth is, they need every bit of the meager money it brings.

“A lot of times we’re running really short,” said Mims, a retired factory worker.

Owens, a retired nurse, has COPD and has to bear the costs of oxygen and 13 different medicines. She doesn’t qualify for food stamps.

“I see more senior citizens working because they can’t make ends meet,” Owens said. “Everything’s going up.”

The pain and the relief were felt far and wide. LINC in Kansas City coordinated LFPA distribution over an 11-county area, reaching towns from Chillicothe to Osceola. Since distribution began in May 2023, LINC recruited and worked with 104 farms that together delivered more than 1.47 million pounds of food that LINC distributed through 94 community sites.

Statewide, according to DSS, 14 Community Partnerships distributed more than $12.3 million in food across Missouri to 476 community sites.

The food goes home with people like Tammy Smith and her family who can tell you, she said, “that the struggle is real.”

As Smith rounded up her two sons, 9-year-old Tao and 6-year-old Tylan, from LINC’s Caring Communities program after school in Hickman Mills, the boys laughed as the family talked of what would come of the latest gift of eggs and meat.

Smith has been making omelettes using the gifted hamburger instead of sausage, and the boys love them.

She and her husband adopted the two boys a year ago from the state foster care system. Smith works as a substitute teacher through Kelly Education, and her husband, forced by injury out of his construction work, found a part-time job as a security guard.

“As a mom of children who were in foster care, I know how they worried about food,” Smith said. She knows that fear too, she said, “because, as a child, I worried about food.”

The farmers who joined in supplying the meat, eggs, fruits and vegetables came into the program with feelings of relief as well.

Because many of the farmers face real struggles of their own.

‘Sowing and reaping’

You can’t build cash flow without growing your farm, Aulgur says. And you can’t grow your farm without cash flow.

Dozens of small, local farms in Missouri and neighboring states were struggling through that paradox when the Community Partnerships came calling with the LFPA-funded opportunity to feed local communities.

Erin Moyer of Moyer Farms in Richmond, Mo., in a letter to the state, told of how her husband, Nathan, was working more than 90 hours a week, exhausting himself in the work of building their family farm, struggling in the uncertain world of agriculture economics, “with no guarantee he would even be able to sell the product or get a fair price.”

Erin had gone back to school to get a master’s degree as a nurse practitioner, a daunting endeavor while raising four children, to seek some financial stability for their family.

Aulgur, who grew up in Chicago, was drawn back to the Missouri farmland where he spent much of his summers on his grandparents’ farms. He has tried to make a go in that “niche” of farming, raising fully-grass-fed cattle and free-range chickens.

In Grandview, Mo., John Gordon has built a small non-profit farm, Boys Grow, that puts teenage boys to work, raising crops and tending to chickens.

For these and many other farms, the LFPA program gave them a time of stability that allowed them to grow.

“The LFPA program became so much more than farming,” Gordon said.

The needed income helped, he said. It provided more young people rewarding jobs and, because of the distribution through neighborhood Grandview schools, it allowed the boys to grow food for their classroom peers.

“It wove stronger ties.”

More than 180 farms ultimately became connected to the LFPA program in Missouri, the state reported.

Aulgur recruited three himself. When he saw an opportunity in demand for eggs beyond what his growing chicken operation could meet, he reached out to three neighbors who were also free-range farmers to help fulfill the LFPA supply.

“It was fun to watch people get excited, neat to see the whole process,” Aulgur said. “Call it karma. Sowing and reaping. It’s a good feeling.”

‘The feeding of the thousands’

When the morning rain became a cloudburst, Aulgur backed his trailer deeper up the front walk, closer to the door, to spare volunteers a soaking as they unloaded the boxes of eggs at Morning Star Youth and Family Life Center in Kansas City.

Monta Tindall, retired from the military and the telecom industry, has been helping out for 10 years from Morning Star’s corner at 27th and Prospect in the heart of the city.

“I pray for better days,” he said.

He wishes more people who might support programs like LFPA could see the volunteer crew carrying in the boxes of eggs and hamburger meat and setting it out to be picked up throughout the day by directors of dozens of distribution sites. And then to imagine the families and individuals, one-by-one, coming to the schools and the churches.

“You see them coming to get their boxes of food and you see the smile and joy on their faces when they leave,” Tindall said. “You enjoy that.”

It feels almost Biblical to him. From the Gospels.

“The feeding of the thousands.”

Many of those meals will go out from the community pantry at St. Monica’s Catholic Church in Kansas City. Pantry director Rita Womack knew, as LINC’s Bryan Geddes carried in the eggs and meat, that this was the last LFPA delivery.

The mission of feeding people in need — already a challenge with rising grocery costs — will get that much harder, Womack said.

Harvesters, a major food bank in the area, has cut back, she said. St. Monica’s relies increasingly on donations from their church community and Womack’s persistent scouring of grocery store ads for bargains.

“A three-pack of hamburger meat at Sam’s used to cost twelve or thirteen dollars,” she said. “Now it costs more than twenty.”

So she’s always searching for bargains to stretch donation dollars as far as they will go.

“I saw hot dogs selling for 99 cents a pack and I went crazy.”

Eggs, cheeses and meat in particular have become too expensive for the pantry to supply for the more than 300 families who sign up for help, she said. The LFPA deliveries through LINC had relieved much of that stress.

Meanwhile, every week more families have been coming to St. Monica’s for help.

“There is food insecurity out here,” Womack said. “And it’s growing.”

What children know

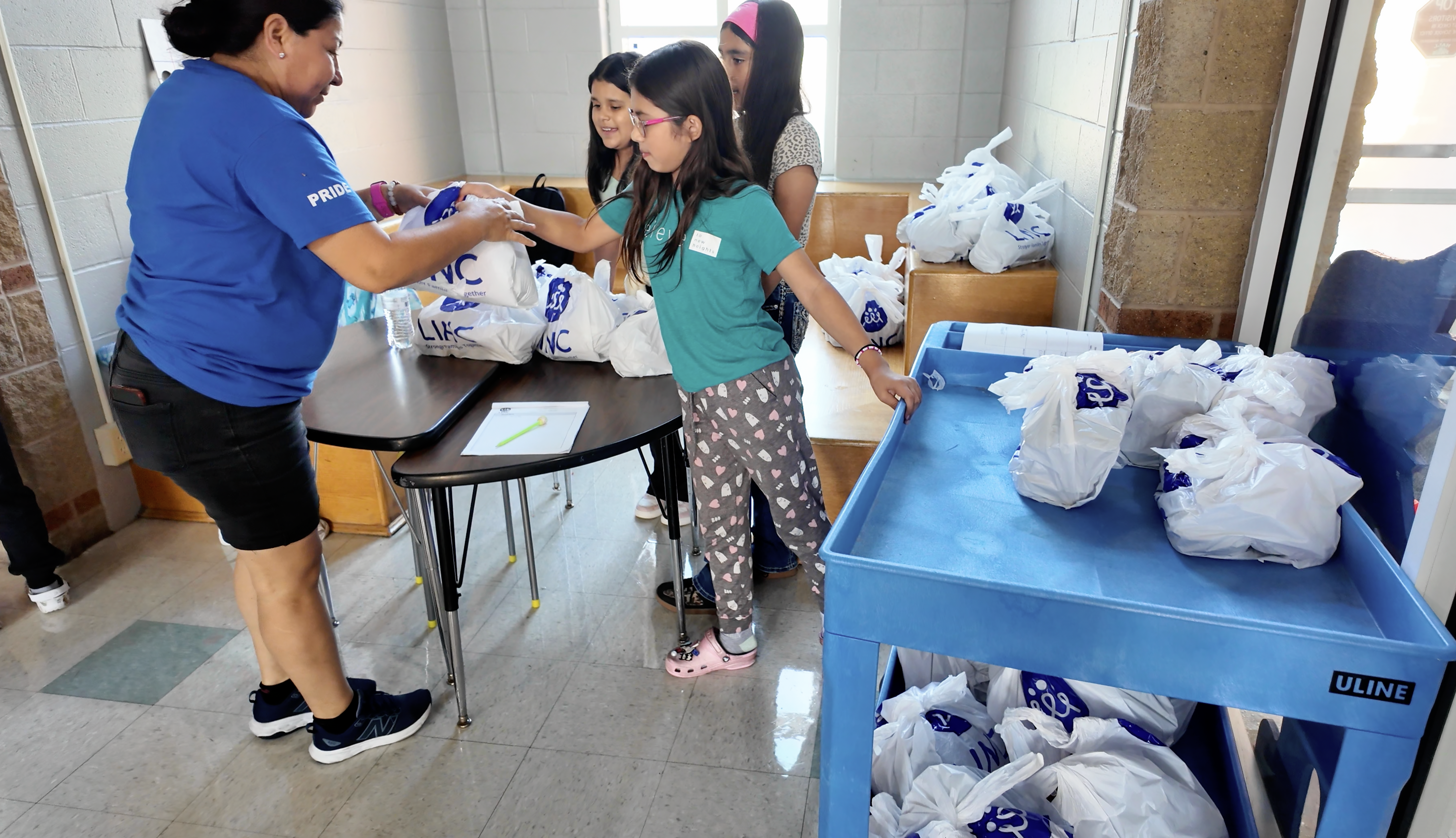

This is what 11-year-old Bryanna and her sixth grade friends Valeria and Brithany think about when they help hand out the monthly bags of food after school at Trailwoods Elementary School in Kansas City.

They think about the faces of schoolmates at lunch time.

They know what it means when another child is asking for — and then stashing — food that classmates are leaving on their lunch trays.

“They’re hungry,” Bryanna said.

She always volunteers to help sort and bag the food, then hand it out to parents in this Northeast Kansas City neighborhood as they leave with their children after school.

Some graciously say “no thank you,” leaving more for others. The many who accept simply record their names, but need not fill out any forms or answer any questions.

“It’s peaceful and nice,” Bryanna said, “giving food to families.”

At King Elementary, the grandparent tutors, Owens and Mims, are joined in the school’s break room by kitchen workers Christina Wilson and Tilease Sims.

The topic of food costs, of struggling, of trying to feed family members in need, hits home with them.

Wilson lives with her aunt whose social security income, she said, isn’t enough to get her through the month.

“I help as much as I can,” Wilson said, “but everything’s going up, way up.”

“We run out, ” her co-worker, Sims, said.

The four talk about having to sometimes pick which unpaid bill they try to carry over to the next month.

Wilson and Sims, likewise, had been relying on the regular LFPA food distribution to help make it to the end of the month.

“We actually just really appreciate it,” Wilson said.

In Hickman Mills, Tammye Fulsom took up the bag of food from a LINC staffer, grateful again, but not aware it was the last.

“The food always comes at a time when I really need it,” she said, “when I got the bills paid but don’t have much left for meals.”

She holds up the packet of hamburger meat.

“You can do wonders with that,” she said. “You all always give the best hamburger meat.”

In the next moment, she learns that the meat and the eggs have been coming from local farms, and that the funding had ended.

Fulsom contemplated the news for a moment.

“Well,” she said. “Tell the farmers thank you.”

Read more