The word is getting around, says Kansas City Municipal Court Judge Martina Peterson.

There is a safe place where your outstanding warrants won’t get you arrested. Where you can get a box of food and some clothes if you need them. Where court officials, out here in the neighborhood and away from the intimidation of the courthouse, simply want to help troubled people be whole again.

This is what Peterson hoped for when the judge created a monthly “Community Court” away from downtown, placing it here in the Morning Star Youth and Family Life Center at the corner of 27th Street and Prospect Avenue in Kansas City, pairing it with LINC Caring Communities and the many support services the center provides.

The doors were open for the February session and many of the people who would get their names on the two-hour docket were walk-ins. Many carried old charges, unpaid fines and fees, that had triggered arrest warrants.

“A lot of people are afraid to take the first step,” Peterson said.

She had seen the effects of that fear in her time presiding over some of Kansas City’s special courts downtown — like mental health court, and drug court. People with already-broken lives were ducking the justice system because they couldn’t pay fines and, fearing arrest, were crippling any chance they had to get a job or seek services they needed to get a new start.

Flyers, social media posts and word-of-mouth helped spread Community Court’s promise when it opened in June 2025. With no danger of arrest, people could come into the Morning Star center and learn the depth of any charges held against them, and in many cases, get them resolved.

Peterson had heard of community courts in some other cities and was part of a team that visited a court in Austin, Texas. She was considering locations for a court when she talked with Missionary Baptist Church Pastor John Modest Miles early in 2025.

Peterson had become familiar with the church’s center — a LINC Caring Communities Site — while attending some of the regular Urban Summit meetings held there. And Pastor Miles was eager to help make the court happen.

It was a perfect set-up, Peterson said. Here was a trusted church center in the heart of the city, right off the Prospect Avenue bus line, with LINC’s wrap-around services and community connections on hand. She knew “people would feel comfortable here.”

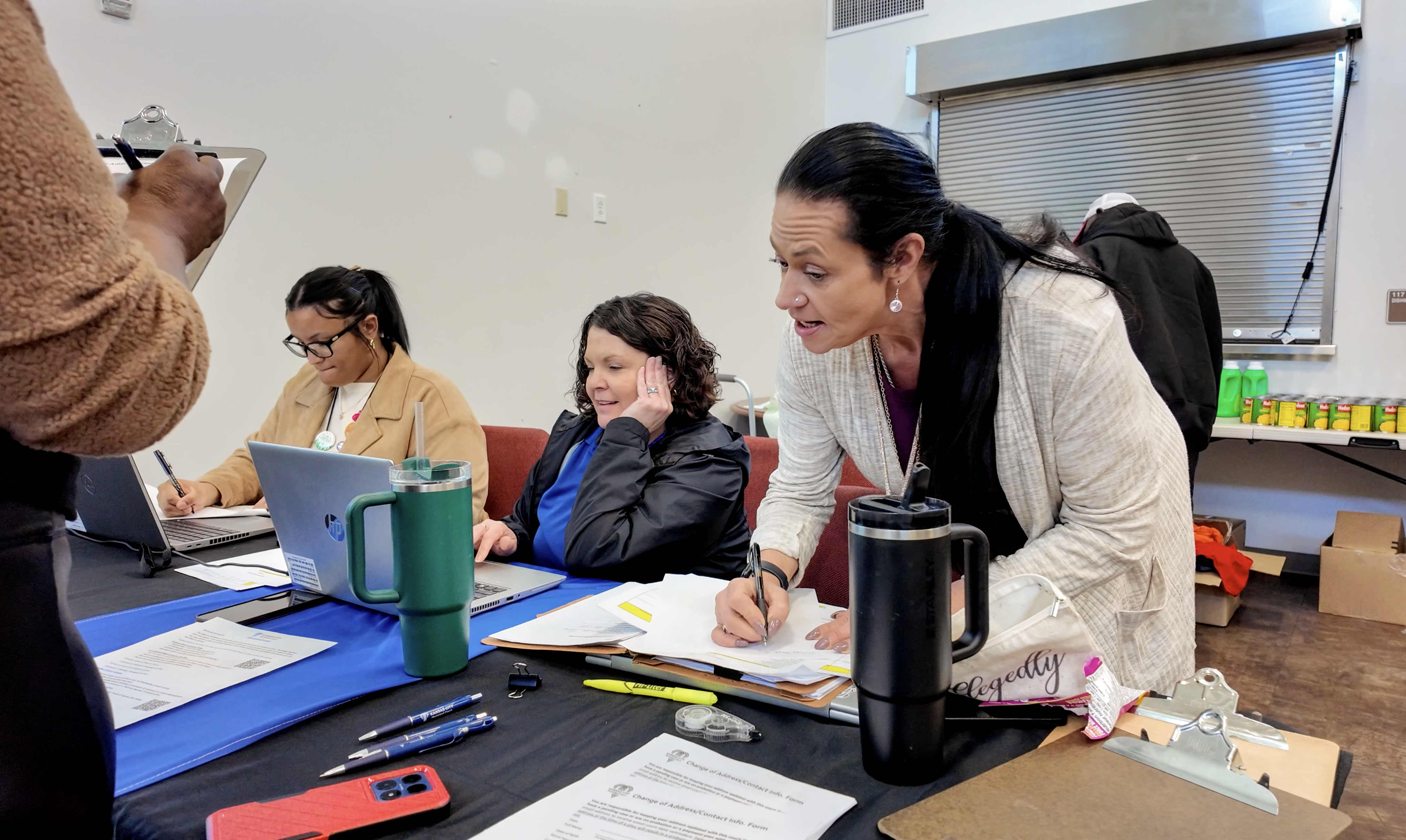

Of the some two dozen people on February’s docket, many had returned from the month before, having been matched with the free services of Legal Aid of Western Missouri, ready to resolve their cases. In some cases, Peterson dropped fines in exchange for community service hours. Others agreed to payment plans.

So many of the people in these difficult situations had old traffic violations, driving with a suspended license and other mistakes or bad choices they couldn’t put behind them, said Lillian Mehler, the staff attorney with Legal Aid. With a stack of manila file folders in her hands, she shuffled between the courtroom setup in Morning Star’s multi-purpose room and a private office where she met with each new client.

“Warrants are scary because people think that’s how you end up in jail,” Mehler said. She knows that many of her new clients “have a bad impression of the system,” she said, “but there are people here who are looking out for the community . . . Everybody’s goal is to help people move to a more positive place in their life.”

It’s a team effort. City probation managers are helping navigate the court records. The city’s Division of Unhoused Solutions has a specialist connecting people to special services. Heartland Center for Behavioral Change has a case manager here. And LINC’s Caring Communities team has stocked tables along one of the walls with clothing, dish detergent, baby items and canned and packaged food that many of the court visitors will take home in boxes.

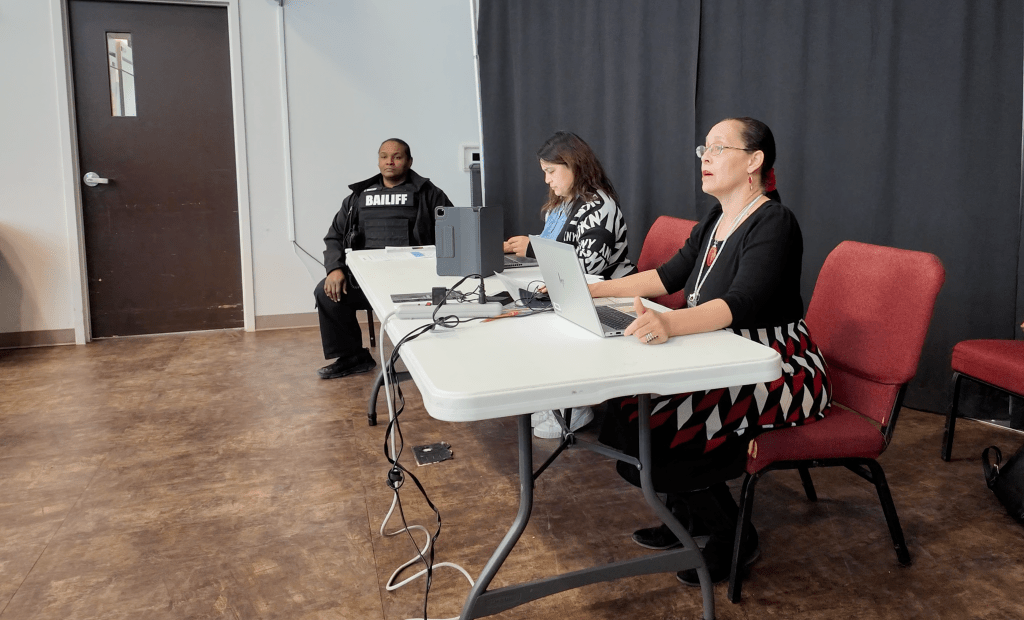

Though set in a church, it is still “court.” The city has one of its prosecutors linked in virtually, ready to explain charges and negotiate pleas. And a black-uniformed bailiff stands ready when necessary to remind the audience of courtroom decorum.

Some of the walk-ins learn that their warrants and outstanding cases aren’t city charges, but state charges from county courthouses. The Community Court team can offer information and some guidance, but cannot resolve state cases. And some city charges, such as any case involving domestic violence, have to be heard in the downtown courthouse.

In all cases, Peterson and the Community Court team want to help put people at ease. The judge wears no robe over her dress and she wields no gavel. Miles, as Morning Star’s minister, already knows or gets to know many of the people who come through the court. Many do their community service hours at Morning Star. He knows Peterson’s court is making a difference.

“She’s a jewel, helping people in the community,” Miles said.